History

1920

Flushing Meadows was first used as an ash dump.

1939

Our site opened as the New York City Pavilion.

1946

We housed the General Assembly of the United Nations.

1964

We welcomed the whole City of New York between our walls.

1972

The Queens County Art and Cultural Center was born.

2013

We transformed into the space you see today.

1906-1935

Dutch rule over New Amsterdam ended in 1664, and Queens County was created in 1683. During the Revolutionary War, Declaration of Independence signer Francis Lewis lived in Flushing. The British used the Quaker Meeting House as a hospital. In the 19th century factories and railroads brought new activity to Queens. By 1900, Queens’ population was 153,000. The Queensboro Bridge opened in 1909, and the elevated railroad along Roosevelt Avenue opened in 1917; by 1920, the population reached 500,000.

Flushing Meadows was undisturbed for centuries until 1906, when the Brooklyn Ash Removal Company bought tracts of it to use as a dumping ground for 50 million cubic yards of burnt refuse. By 1934 one mound in the dump was 90 feet tall and nicknamed “Mount Corona,” and the site was an environmental disaster.

However, at that time, a young Robert Moses was intent on linking Long Island to Manhattan. He built the Grand Central Parkway in 1932, but could not obtain the financial support to transform the ash dump into what he believed would be the ideal New York City park—until one evening, when two Queens businessmen began to discuss a New York World’s Fair…

The Corona Ash Dumps were vividly described by F. Scott Fitzgerald in his novel The Great Gatsby from 1925:

“About half way between West Egg and New York the motor-road hastily joins the railroad and runs beside it for a quarter of a mile so as to shrink away from a certain desolate area of land. This is a valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens, where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of grey cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-grey men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud which screens their obscure operations from your sight…”

The valley of ashes is bounded on one side by a small foul river, and when the drawbridge is up to let barges through, the passengers on waiting trains can stare at the dismal scene for as long as half an hour.

1939-1940

The New York City Building was built to house the New York City Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair, where it featured displays about municipal agencies. The building was centrally located, being directly adjacent to the great icons of the Fair, the Trylon and Perisphere, and it was one of the few buildings created for the Fair that were intended to be permanent. It is now the only surviving building from the 1939 Fair. After the World’s Fair, the building became a recreation center for the newly created Flushing Meadows Corona Park. The north side of the building, housed a roller rink and the south side, an ice rink.

The building’s architect, Aymar Embury II, was one of Robert Moses’ favorite designers and his other work includes the Central Park Zoo and the Triborough Bridge. He designed the building in a modern classical style, which was perhaps a little ironic given that the theme of the 1939 Fair was the “World of Tomorrow.” The exterior of the building featured colonnades behind which were vast expanses of glass brick punctuated by limestone pilasters trimmed in dark polished granite. The solid corner blocks were also constructed from limestone.

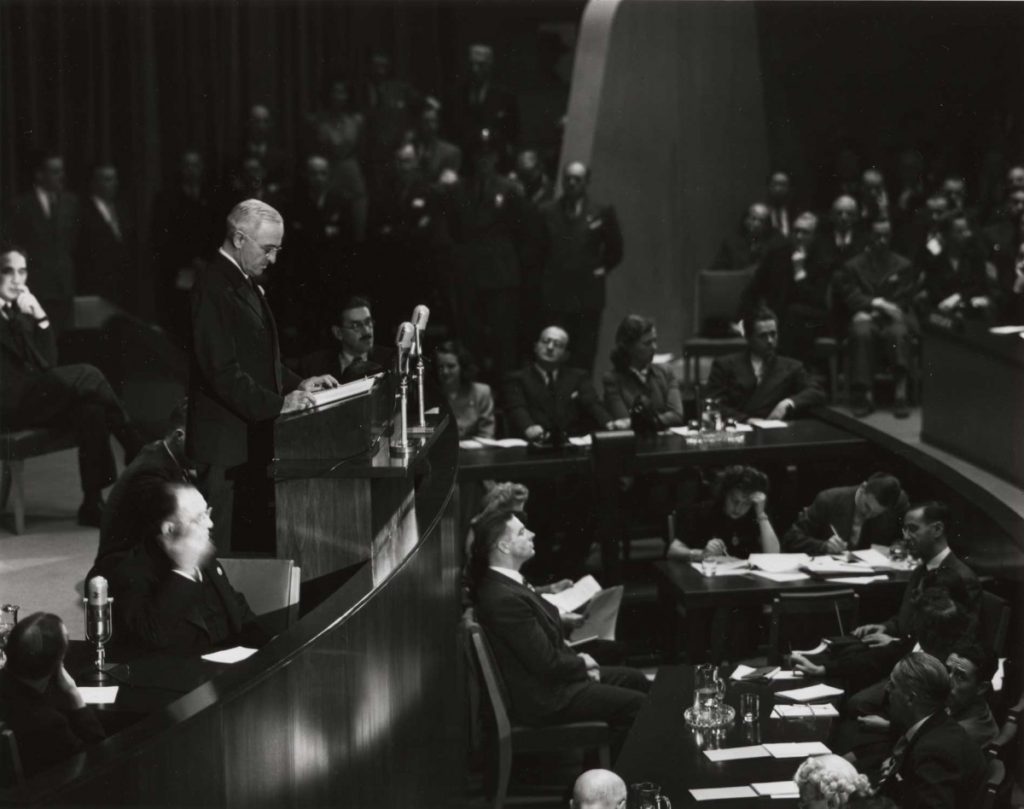

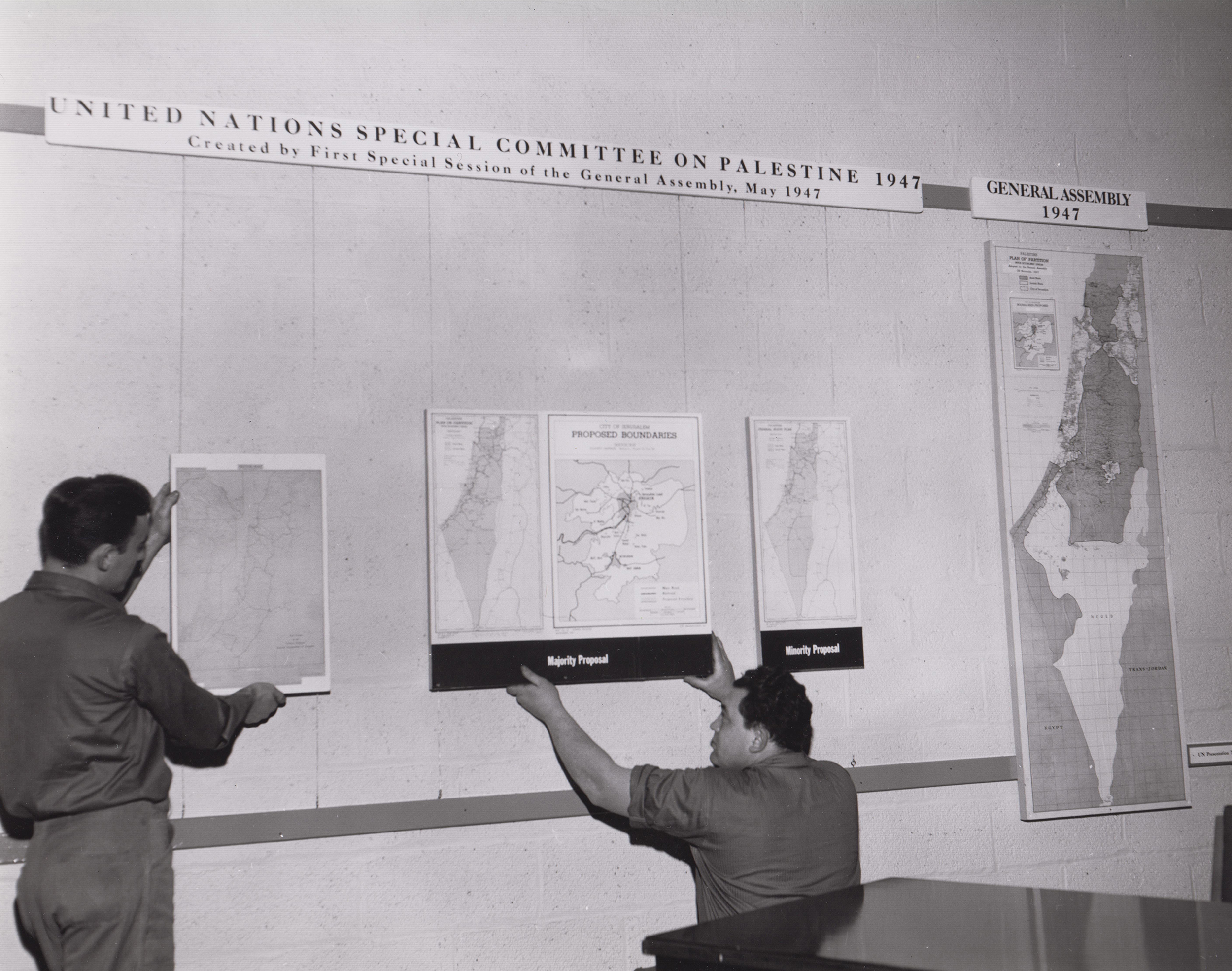

1946-1950

One of the proudest periods in the history of the New York City Building was from 1946 to 1950 when it housed the General Assembly of the newly formed United Nations. Until the site of the UN’s current home in Manhattan became available, Flushing Meadows Corona Park was being considered as the organization’s future permanent headquarters site. During the early post-war years, almost every world leader spent time in the New York City Building and many important decisions, including the partition of Palestine and the creation of UNICEF, were made here.

The presence of the General Assembly of the United Nations in the building required substantial interior renovation and the addition of a sizable annex on the north side of the building housing the delegates’ dining room, the public cafeteria and an exhibition hall. In the interior, the skating and roller rinks were covered and, in the space now occupied by the Queens Museum’s sky-lit galleries, the General Assembly was laid out. Offices; meeting rooms; translation, press, radio, and television facilities; and other services were located through the rest of the building. When the United Nations left, the external annex was removed and the New York City Building again became a recreation site for the Park with the ice skating and roller rinks restored.

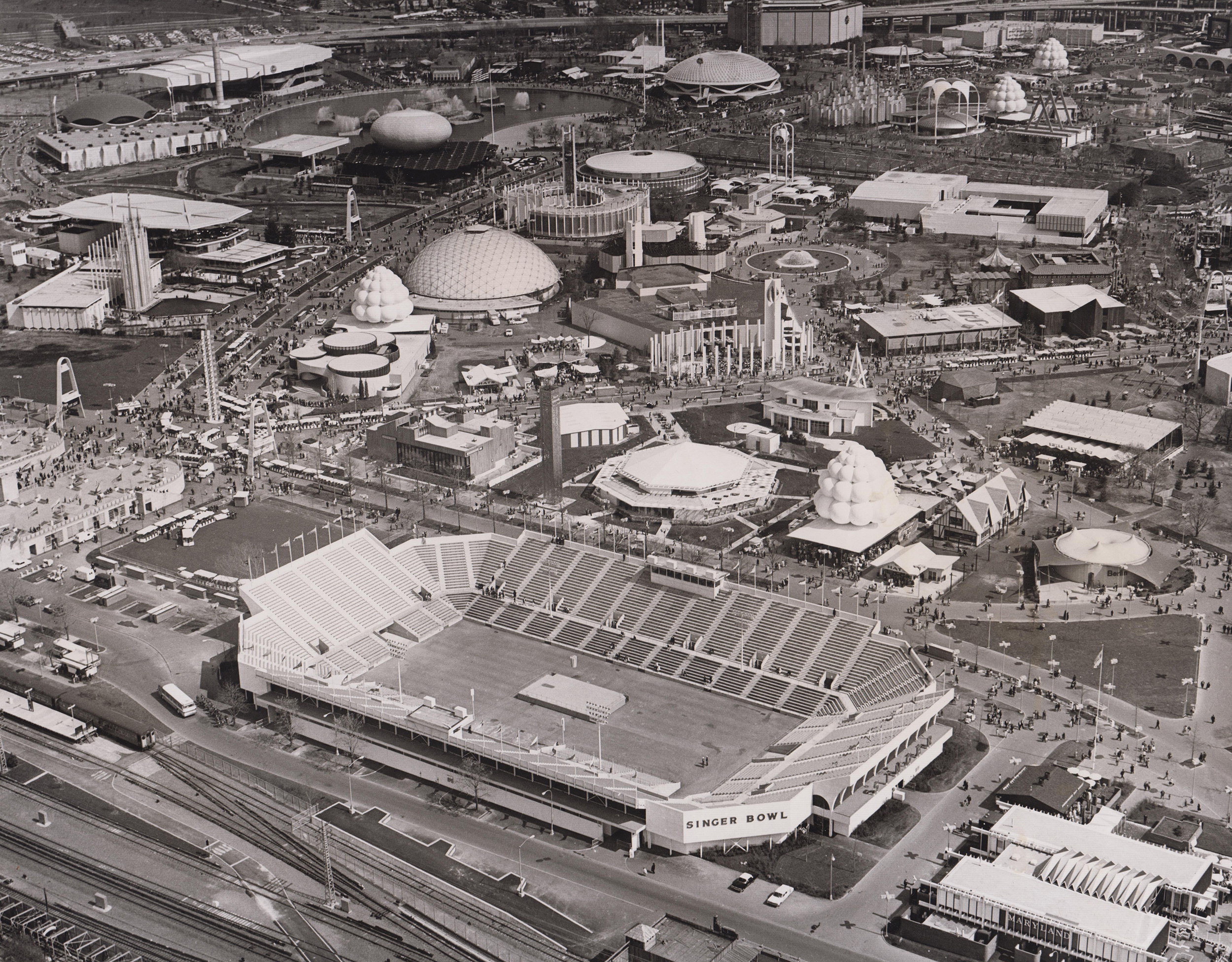

1964-1965

In preparation for the 1964 World’s Fair, the New York City Building was again renovated. Under the architect Daniel Chait, a scalloped entry awning was added to the east façade with concrete brise-soleil used to screen all of the areas of glass brick. The building once again housed the New York City Pavilion and the most dramatic display there was The Panorama of the City of New York. Commissioned by Robert Moses for the 1964 Fair, in part as a celebration of the City’s municipal infrastructure, this 9,335 square foot architectural model includes every single building in all five boroughs. The Panorama remains in the building and open to the public as part of the Museum’s collection.

As in 1939, the New York City Building was at the center of the 1964 World’s Fair. It was (and still is) adjacent to the 140 foot high, 900,000 lb. steel Unisphere—that great symbol of the Fair’s theme of “Peace through Understanding.” After the Fair, The Panorama remained open to the public and the south side of the building returned to being an ice rink.

1972-2008

In November of 1972, the Queens Museum (originally named the Queens County Art and Cultural Center) opened to the public with 19th Century American Landscape Paintings, an exhibition of loaned works from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. Housed in the New York City Building, originally built by Aymer Embury II for the 1939–1940 World’s Fair, the Museum was inaugurated as a 501(c)(3). The inauguration of the Museum was spearheaded by the Queens Council on the Arts under the guidance of Wallace West and a number of Queens residents, cultural workers, and public servants. As a nascent arts institution, the Queens Museum did not have a formal collection and took advantage of the Met’s desire to decentralize its activities, sharing portions of their collection with cultural sites in the outer boroughs. This relationship enabled a unique merger of historical and contemporary exhibitions to arise at the Queens Museum. The Panorama of the City of New York, the 9,335-square foot model of New York City, inhabited the majority of the building; the Museum occupied the northern half of the building while the southern half remained an operational ice skating rink. On the second floor outside of The Panorama, exhibitions originally conceived of and installed for the 1964–1965 New York World’s Fair by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) remained on-view until 1978. The TBTA was led by Robert Moses until 1968, and these installations spoke to the activities and projects he’d initiated under his thirty-year tenure there.

Despite some difficulties around the Museum’s founding, major exhibitions such as Homage to Joseph Cornell (1973) and They Also Ran, an exhibit documenting the mayors of New York City since 1898, were early triumphs in programming. Queens Talent ‘73 was the first in a long line of exhibitions dedicated to highlighting emerging artists from Queens: these installations continued to appear at the Museum through the present day (Queens Artists, 1975–80; Queens Annual, 1981–82; Annual Juried Exhibition, 1983–89; Queens Invitational, 1990; Queens International, 2002–18). The Museum’s engagement with students in Queens also began in this era with the exhibition Queens High School Artists (1974), and collaborations with educational art programs appeared annually in the galleries. With fewer than ten employees for the majority of this first decade, the Queens Museum mounted many exhibitions that were borrowed from outside institutions. This facilitated an assortment of subjects and artistic practices in the gallery spaces including West African art, Indian miniatures, Puerto Rican contemporary prints, Peruvian ceramics, Chinese calligraphy, Navajo weaving, and art from Indigenous communities in what is now known as Alaska, in addition to local contemporary sculpture and photography.

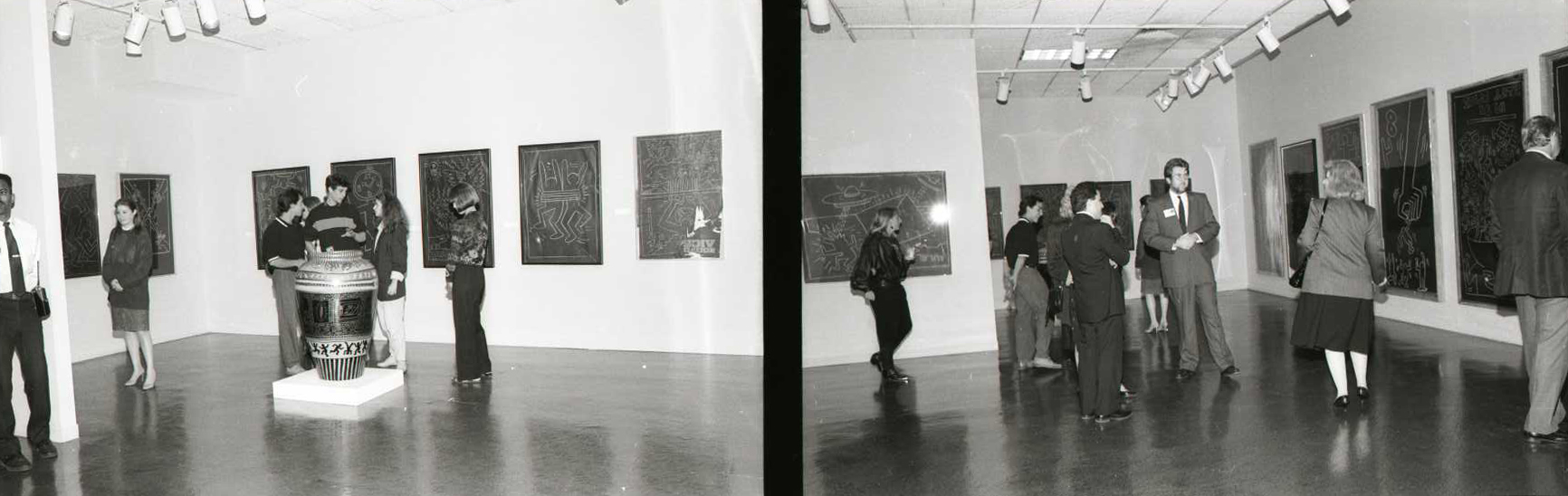

Throughout the 1980s, the Queens Museum hosted film screenings, musical performances, lectures, and art-making workshops for children and adults. Historical shows selected from the Met Museum’s collection or traveling from museums across the country continued as a collection was slowly being built on-site in Queens. Exhibitions including Circa 1800: The Beginnings of Modern Printmaking 1775–1835 (1981), The World of Japanese Theater (1983), and Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in 19th Century America (1988) proved a continued interest in uplifting the Queens community by way of access to a range of artistic styles and interpretations. An engagement with contemporary art continued: the Queens Museum hosted the first New York institutional solo exhibitions for Alex Katz (1980), Laurie Anderson (1984), and Keith Haring (1990) after his untimely death due to the AIDS epidemic. There were also important group exhibitions—Made in Queens (1983, celebrating Queen’s Tricentennial), The Real Big Picture, and Television’s Impact on Contemporary Life (both 1986)—that showed the ways in which art was becoming embedded in our daily lives. Major figures in the artworld including Alison Saar, Whitfield Lovell, Kenny Scharf, Barbara Kruger, Nam June Paik, Bruce Davidson, and Bruce Nauman, among others, left their mark on the Queens Museum during this experimental era. At this point, Queens Museum also welcomed exhibitions dedicated to the World’s Fairs and it’s burgeoning collection, such as Dawn of a New Day: The New York World’s Fair 1939/40 (1980), Recent Acquisitions (1984), and Remembering the Future: The New York World’s Fairs from 1939 to 1964 (1989).

In the 1990s, in anticipation of the Museum’s 25th anniversary, several significant renovations were completed including an upgrade to the museum’s galleries by Rafael Viñoly (1990–94) and a comprehensive update of The Panorama of the City of New York (1992–94) by Lester Associates, the original fabricator of the model. In fall 1992, the Museum inaugurated the reopening of its galleries with Fragile Ecologies: Contemporary Artists’ Interpretations and Solutions, one of the earliest contemporary art exhibitions that addresses climate change through the lens of artists. Viñoly’s renovations also included a new glass walkway around the perimeter of The Panorama, replacing the original “helicopter ride” from the 1964–1965 World’s Fair, and radically enhanced the viewing experience of the mode. The original glass windows on the second floor, formerly the only mode from which most visitors could view the model after the Fair closed in 1965, were removed and ushering in a new era at the Museum. The updated Panorama debuted in Summer 1994, reflecting New York City as of January 1, 1992. Shortly thereafter in 1995, the Museum partnered with the Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass in Long Island City to present portions of the collection within the Museum, with the first presentation taking place in 1997. This Neustadt Collection continues to curate annual exhibitions consisting of artifacts, tools, and original lamps.

New endeavors arose both within and outside the Museum’s walls. A partnership was initiated with Bulova Corporate Center (formerly of Bulova Watch Company) to exhibit emerging artists in their lobby for several months at a time. This initiative continued through the early 2000s, and embraced artists Bing Lee, Chakaia Booker, Denyse Thomasos, and Isidrio Blasco, among many others. On-site, the trailblazing series “Contemporary Currents” (1991–97) arose to exhibit multicultural, international artists such as Christian Boltanski, Ik Joong Kang, Sarah Charlesworth, Cai Guo-Qiang, and Candida Alvarez. Important solo projects by Mel Chin (1991), Luis Cruz Azaceta (1991), Barbara Ess (1993), Yukinori Yanagi (1995), Dawoud Bey, and Robert Colescott (both 1998) were accompanied by the groundbreaking thematic exhibitions The View from Within: Japanese American Art from Internment Camps (1995), Live/Work in Queens (1995), and Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy (1995). Several exhibitions collapsed the distance between traditional, historical, and contemporary art forms from varied regions and diasporas that enrich Queens, most notably Ante America (1993), Across the Pacific: Contemporary Korean and Korean American Art (1993), and Out of India: Contemporary Art of the South Asian Diaspora (1997). The Museum’s millennium show, and one of its most ambitious and celebrated undertakings, was Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s (1999). The exhibition was an international survey of regionally-specific conceptual art practices, chosen by eleven curators and art historians from each locality, that considered the socio-cultural origins and contexts surrounding the artists included.

As a new millennium came to pass, the Queens Museum remained committed to showing contemporary art alongside significant considerations of the Museum’s history and site. Series including “Art Zone,” “Video Cafe,” and “Community Space” made room for interactive, tactile exhibitions and community-led initiatives. Public programs and educational share-outs started in Corona Plaza as early as 2005, inspiring the Heart of Corona Initiative in 2007 which led to collaborative work with community leaders and organizations, residents, elected officials, and business owners to make the neighborhood surrounding the Museum better. Off-site engagements and exhibitions were mounted in Corona Plaza until 2008. Back in Flushing Meadows Corona Park, series such as “Wall Work,” “Ramp and Wedge,” and “Queens Focus” were dedicated to emerging local artists fabricating site-specific interventions within the Museum. Tapping into New York City’s rich history, significant solo exhibitions by Joan Jonas (2003) and Yue Minjun (2007) complemented prismatic group exhibitions including Translated Acts: Performance and Body Art from East Asia 1990 to 2001 (2001), Fatal Love: South Asian American Art Now (2005), and Generation 1.5 (2007). The Museum’s site and its collection produced deeper connections to New York City’s urban history by way of exhibitions such as Designing the Future: The Queens Museum of Art and the New York City Pavilion (2002), The Seeing Eye: Art and Industry at the 1964 World’s Fair (2004), and Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Road to Recreation (2007) (with Columbia University and the Museum of the City of New York).

In 2008, the Queens Museum began the first portion of a major renovation project to rejuvenate the gallery spaces and expand the footprint of the Museum. Conceived and implemented by Grimshaw Architects in collaboration with Ammann & Whitney, this upgrade would transform that space into an open floor plan. Five additional galleries, a gigantic central atrium, and a glass staircase connecting the first and second floors were important components of this endeavor. The Museum you see today is a result of this incredible upgrade, facilitated by a Capital Construction Grant provided by the City of New York. The Museum did not close in its entirety during this period, and continued to mount enticing exhibitions. During this time, The Relief Map of the New York City Water Supply System was also exhibited for the first time on-site. In 2008, after a three-year collaboration with the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to conserve it, the object was brought to the Queens Museum alongside significant archival materials from the NYC Municipal Archives for A Watershed Moment: Celebrating The Homecoming of the New York City Water System Model. It remains on-view today, providing a connection to the complex systems that maintain New York City’s populace.

2013-Today

November 2013 ushered in a new phase in the institution’s history. The Museum officially removed the qualifier “of Art” to become known as the Queens Museum, making direct reference to the variety of cultural, historical, and social components inherent to the program. The completed expansion project begun by Grimshaw Architects in 2008 removed the storied ice skating rink to provide an additional 50,000 square feet, doubling the Museum’s footprint. A gigantic central atrium surrounded by exhibition space on the perimeter was capped by a 40-foot-tall wall on the exterior of The Panorama of the City of New York, providing a new surface for experimental commissions. A new entrance to The Panorama connected to the atrium space was also added, allowing visitors to see into The Panorama and view the model from “sea-level” for the first time. New plate-glass facades on both sides of the building’s exterior allowed visitors to see through the space and into Flushing Meadows Corona Park. On the second floor, several galleries were refinished as flexible space to be used by the Museum’s Education and Public Programs departments.

Just before the renovation, the Museum debuted The Relief Map of the New York City Water Supply System, a long-term loan from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). After the expansion, the model was moved into one of the new galleries, offering a generous prompt to and ample space for contemporary artists considering water, natural resources, and infrastructural connections to the rest of New York State. The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass was also moved into a new gallery on the first floor. Rounding out the first floor additions, a new Museum shop and café were constructed adjacent to the Museum’s new front porch—an extended outdoor area with twelve crape myrtle trees and outdoor seating for museum-goers and park users alike, leading to a large lawn for outdoor programming.

To inaugurate the Museum’s reopening, the World’s Fair Visible Storage opened on the second floor with 900 artifacts, souvenirs, and commemorative objects related to the 1939–1940 and 1964–1965 New York World’s Fairs. Artist Pedro Reyes assembled The People’s United Nations (pUN), gathering 193 New Yorkers from the 193 nations represented in the famed organization which was initiated within the New York City Building (1946–50) to consider strategies of conflict resolution. The sixth iteration of Queens International and Citizens of the World: Cuba in Queens were also on-display to mark the reopening of the 105,000 square foot Queens Museum. Peter Schumann, the legendary founder of the Bread and Puppet Theater in the 1960s, was also a part of the reopening program, uniting performance and art circles in New York City by way of his solo exhibition, The Shatterer. Schumann was the first to compose a monumental wall drawing directly on The Panorama’s exterior wall, facing the spacious, light-filled atrium.

Several small galleries on the second floor of the rejuvenated Queens Museum, connected to the ground floor by a fluid glass staircase, give space to community investments the Museum has long cultivated. Overlooking the iconic Unisphere, these galleries host family education workshops, exhibitions, and varied programs and events throughout the year. Since 2013, the space has hosted collaborative exhibitions with the COPE NYC (2013), the Taiwanese American Artists Council (2014), Korean Cultural Service of New York (2014), Make the Road NY (2015), Immigrant Movement International (IMI) with Tania Brugera (2016, 2017), the National Alumni Association of the Black Panther Party (2016), New Workers New Yorkers (2018), and the Artistic Freedom Initiative (2018), among others. It has also been a space where students and young people can display their art as a part of the Museum’s ArtAccess programs and varied partnerships with New York City schools under programs including the Cultural After School Adventures (CASA) Initiative.

Within this new floorplan, what was originally the entirety of the Queens Museum has been transformed into nine distinct studio spaces for artists. Occupying the northern side of the Museum’s first floor, these studios range in size from 350 to 700-square feet. When the Museum reopened, the “Queens Museum Studio Program” (2013–15) hosted artists as well as a series of networking lectures, retreats, workshops, film screenings, dinners, and professional development sessions. As the artist-in-residence program developed, the Queens Museum had the pleasure of hosting a wide range of artists and practices, including Onyedika Chike (2015), Caitlin Keogh (2015), Chris Bogia (2017), and Wang Tuo (2017). Queens Museum also started a partnership with the Jerome Foundation to provide emerging artists with a grant for new work, and supported individuals including Kameelah Janan Rasheed (2015), Ronny Quevedo (2017), Sable Elyse Smith (2017), American Artist (2017), and Alexandria Smith (2019).

A plenitude of new space allowed the Museum to present exhibitions that drew the collection into deeper conversation with art history. Bringing the World into the World, a group exhibition of contemporary artists inspired by the Museum’s Panorama to reflect upon representations of the world (2014); 13 Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair (2014); That Kodak Moment: Picturing the New York Fairs (2014); and Never Built New York (2017) specifically considered how artistic practice overlapped with elements of our collections. Exhibitions of historical content that spoke to our local communities were frequent as well, most notably After Midnight: Indian Moderns and Contemporary Indian Art (2015); Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk (2016); The Lavender Line: Coming Out in Queens (2017); and Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas (2019). Major solo exhibitions by established artists including the Los Angeles Poverty Department (2014), Mierle Laderman Ukeles (2016), Patty Chang (2017), Mel Chin (2018), Pia Camil (2019), and Suzanne Lacy (2022).

The sightlines offered by the renovation produced one unprecedented site for experimentation: the “big wall” outside of The Panorama, visible from the atrium. Reaching upwards of forty feet into the air, this space became the site of annual commissions by exclusively female artists. Initiated by Mickalene Thomas in 2015, the program continues to this day and has included Mariam Ghani (2016), Anna K.E. (2017), Heidi Howard and Liz Phillips (2017), Ulrike Müller (2019), and Christine Sun Kim (2021).

Most recently, Queens Museum has continued to push the possibilities of combining studio practice, community engagement, educational programs, and exhibitions through initiatives including the Year of Uncertainty Artist Residency Program (2020–21) and the In-Situ Fellowship program (2023–25). By hiring artists to work among staff across various departments at the Museum, we continue to explore and redefine what it means to be a porous “community museum” with enhanced access and accountability to our audiences.