| Janet Henry |  |

|||

| The ideas behind the Twos started percolating in the early 1990s, when I taught art at the Lower Lab School in Manhattan. The fourth grade was studying Northeast Native Americans, so I came up with the idea of creating objects that represented symbols of authority. That was it until ten years later when the contrarian in me decided if I used the jewelry form to make my art instead of making actual jewelry, practicality could take a hike and it would be way more interesting to go where the material and my inspiration took me. As with the "real" jewelry I make, the forms I pursued were based on sketches made from the book How to Wrap Five Eggs: Traditional Japanese Packaging by Hideyuki Oka and a non-verbalized fascination with undersea creatures and habitats. The Twos became another one of my "what ifs?" Like "What if I combine two ostensibly disparate elements for no reason other than I want to see what will result?" I found forty-one terms for "two" and set about making a piece for each one. They are personal evocations— not declarations. Turns out rather than representing outward status, they are symbolic of the internalized sense of self, a signifier—something that brings you around to yourself. |

||||

|

||||

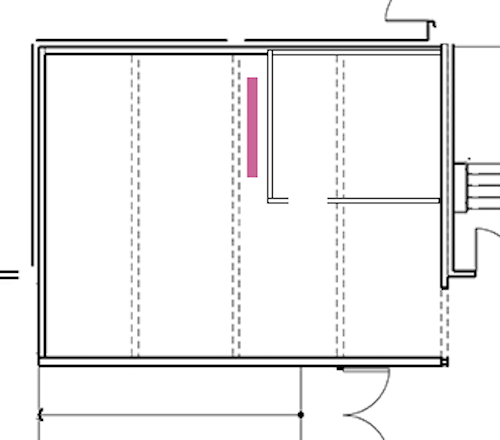

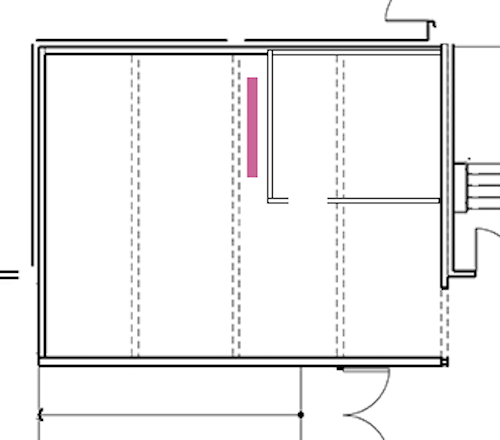

| Previous exhibition installations unfortunately made the work look like cadavers dangling from hooks. Expressing my displeasure with how the Twos had come off got me sage advice from Carrie Mae Weems: "Put them in Joseph Cornell-like boxes." I'm using the form but not the aesthetic—2D collages line the boxes the Twos will be displayed in. I was sitting on the dining room floor of Linda Goode Bryant's apartment trying to do something with a couple of the action figures I was using at the time. I remember laughing out loud at a scenario I cobbled together and David Hammons muttering, as he walked through the room, "How come she has so much fun making her stuff?" I like that I can surprise and amuse myself. Placing blue eyes and pink lips cut from magazines on a full-page photograph of Glenn Lowry and having it turn into Charlayne Hunter Gault was just antic. I continuously collect collage material for my classes. Isolating facial features so that they can be reassembled, Face Morphing, developed into a project I could do with the lower grades. The focus in my work however has been more than altering faces: the entire picture plane comes into play. If they seem polemical ("Is this what we eat?") it's unintentional. They're simply juxtapositions of seemingly unrelated subject matter, again. I take pride in having stuck a baked turkey on the head of some actress. I know I'm supposed to have a more complex and theoretically-vetted rationale for my creative pursuits, but I don't. The idea of posing the same questions and resolving each one of them in the same manner is horrifying to me, but novelty for its own sake doesn't particularly capture my imagination either. |

||||

|

I play mostly classical music in my classes. I love J.S. Bach and Sibelius but the kids recognize Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf and The Nutcracker by Tchaikovsky which is a vindication of sorts. Even complaints that I put on Ravel's Le Tombeau de Couperin too much means they're hearing it. At one point I found out that a student could play that finger-breaker "Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum" from Debussy's Children's Corner Suite. Her friend recognized it from a recital she had attended. My student described the experience as fun. I heard "easy" but she didn't let that mistake lie for long. I realized why: there is nothing like the elation (or "fun") of nailing something. That's my primary aim when I teach. I try to provide an environment where students can have as much fun as I do when I make art; that they're comfortable with the tools I ply them with—natural ability or not—and they can fabricate whatever they want. Bach's back-story taught me that; practicality can create ethos and it can be a muse. |

|||

| prev | Janet Olivia Henry (b. 1947, New York, NY) received a scholarship to School of Visual Arts, and earned an Associate Degree from Fashion Institute of Technology (1969). She was a recipient of a Rockefeller Fellowship in Museum Education at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1974). She has exhibited her work in solo and group shows at AIR Gallery, NYC, Boston Institute of Contemporary Art, Albright Knox Museum, Buffalo, NY, (2018), Brooklyn Museum of Art, California African American Museum, Los Angeles, (2017), Jamaica Arts Center, NYC, (2014), PPOW, NYC, (2002), Exit Art, NYC, (1999), The Drawing Center, (NYC) (1996), Hallwalls, Buffalo, NY (1995), New Museum, NYC, (1994), Artists Space, NYC, (1993), Just Above Midtown Gallery, NYC, (1982), Franklin Furnace, NYC, (1981), Studio Museum in Harlem, NYC, (1981). Henry has served as a Program Associate at New York State Council on the Arts (1987-95) and is currently a teaching artist at Brooklyn Heights Montessori School. Henry lives and works in Jamaica, Queens. | next | ||

| prev | next | |||