| Chris Domenick |  |

||||

| Over the past several years I've been trying to activate drawing and sculpture so it feels like they are cut from the same cloth—integrating these modes of making so they can physically co-mingle. Drawing is inherently associated with plans, whim, gesture. My frames offer stability to otherwise fragile works on paper while operating as objects among objects, like a couch, a chair, or a house plant. This inside/outside dialectic has been central to my work for a long time. I’ve recently come around to thinking about the frame as though it is doing exactly what it is meant to do, and there may be some small transgression in that. What happens if the frame passes as a frame? Maybe it offers a nuanced way of looking at otherwise unwieldy signifiers. | Do these types of household objects that you mention manifest in the work alongside the frame? Can you talk more about the frame being itself versus passing as something else? When it is something else, does it still offer stability? (Of course it does physically, but does it still signify it?) |

Do these types of household objects that you mention manifest in the work alongside the frame? Can you talk more about the frame being itself versus passing as something else? When it is something else, does it still offer stability? (Of course it does physically, but does it still signify it?) |

|||

|

I use these objects as examples to paint a psychic scene, to conjure the presence of other mundane objects, of which a frame is a part. There is a discourse in painting that addresses the tension between surface and support, putting the two at odds—practices of this nature tend to demonstrate the instability of the frame or the support or the insufficiency of the image. I’m interested in engaging with this discourse by thinking about ways in which all the parts of a thing are interdependent, and that somehow there might be a hierarchical restructuring that happens from within. I’m presenting a very known convention that is quietly rejecting its own identity—this is the symbolic instability that relates to larger realities. | ||||

| What should we know about your practice that's not necessarily visible in the work? | That it responds to architecture, the suburban landscape (inside and out), fantasy, and poetry. I’m often using language and deconstructing narrative, to create an alphabet of glyphs that is idiosyncratic and specific to each work. Though like some artists I admire; like Nancy Spero and Moira Dryer the alphabet and archive of signs, surfaces and symbols that I use grow on themselves as I become more practiced, and as the number of individual works I create grow. | What should we know about your practice that's not necessarily visible in the work? | |||

| How do you consider the works in relation to one another? If they are born of the same system, how do you consider grouping them and what they can collectively say, reveal, or suggest? | How do you consider the works in relation to one another? If they are born of the same system, how do you consider grouping them and what they can collectively say, reveal, or suggest? | Each work carries a different amount of information, speed, intention, and legibility, so thinking about them together offers a glimpse into the broader project. Through arrangement, the logic of the work is more accessible—the vocabulary of signs, repetitions, and forms can be read cumulatively. That said, each work attempts to stand alone as a kind of singular by-product of the studio practice. | |||

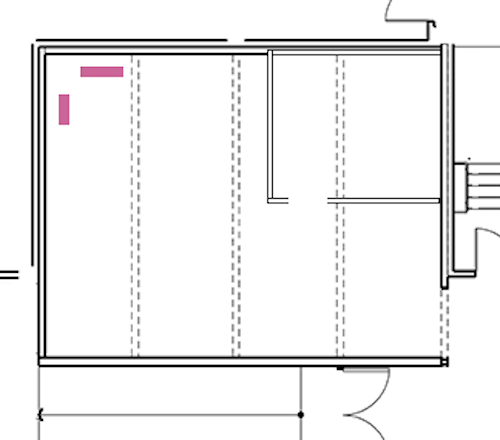

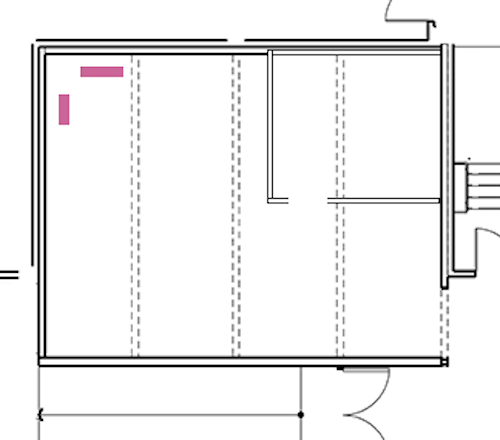

| I am skeptical of the notion of expressive gesture as a clear manifestation of desire, so I tend to inhabit a process where desire is masked under layers of decisions, some of them not totally my own. This process of thinking about the work is directly linked to my personality and my lifelong struggle with addiction which has taught me my desires are not to be trusted. This is in part why I identify with sculptural and architectural histories that have relied on processes of erasing through addition. I’m interested in pre-existing structures that have been awkwardly added to or subtracted from like new vinyl on a deteriorating Blockbuster video sign or a countertop with two different laminate patterns from two different decades. Looking at these forms helps to understand the meandering cycles of authorship in our visible world. Volumes are internal (things we carry around inside of us) and external (things we walk past, drive past, enter). They can be portals to spiritual dimensions or they may just be inaccessible containers, like a locked archive. |  |

||||

| prev | Chris Domenick (b. 1982, Philadelphia, PA) earned an MFA from CUNY Hunter College (2013) and a BFA from Tyler School of Art (2005). Recent solo projects and collaborations were exhibited at venues such as Beeler Gallery, Columbus, OH (2018); MASSMoCA, North Adams, MA (2017); and helper projects, Brooklyn, NY(2017). Domenick has published in Cabinet Magazine (2017). He has been included in exhibitions at Canada Gallery, Skibum Macarthur, The Vanity East, MOMA, Essex Flowers, Situations, Torrance Shipman, Regina Rex, Room East, and Louis B James, among others. He has participated in residencies including The Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program (2015), Recess Activities (2014), and Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2012). He lives and works in Sunnyside, Queens. | next | |||

| prev | next | ||||